Alice, Laurie & Ripley

Lisa Herfeldt4.10–22.11.2025

abject law

Shooting out of a slim columnar base, and, save for its tapered tip, encased in a transparent and likewise cylindrical extension thereof, the elongated milky-skinned ellipsoid thing that is so presented is neither this nor that. Its apparition is too ambiguous, its shape and hue simultaneously eliciting a variety of reminiscences that eventually converge mostly in images more or less vaguely related to body parts and their secretions. This much can be said: neither beautiful nor ugly, and with its possible function remaining unidentifiable, this thing looks both strange and familiar, in other words, it both repels and attracts. Its simple (yet not pristine, indented) shape fails to inspire calm and gradually becomes eerie as ludicrous associations insinuate themselves, along with the uncanny premonition of what its smooth surface might hide in plain sight: a gigantic phallic incarnation/macabre torpedo-shaped larva/lardy anatomical extrusion preserved for display in a cabinet of curiosities? This object would be more so grotesque, were it not for the clean, orderly case, which, albeit on the verge of being creepily subverted, can still provide its onlooker the impression of a safe distance. But not for long, because the sight of the creamy, morbidly soft, skin-like surface brings back an unverifiable feeling of unease. These psychological movements between fascination and repulsion—the push and pull that defines the subject’s relation to certain objects, be they material or metaphorical—are what drive the horror genre.

Lisa Herfeldt makes a direct reference to American horror cinema and its sub-genres when she titles her exhibition Alice, Laurie & Ripley, and one of her works, evoked above, Final Girl. The three iconic female protagonists, here named alphabetically, appeared in a different order on the big screen: Laurie in John Carpenter’s Halloween (1978), Ripley in Ridley Scott’s Alien (1979), and Alice in Sean S. Cunningham’s Friday the 13th (1980). They all marked the beginning of horror sub-genres—sci-fi and slasher—which had been anticipated by previous films, such as Invasion of the Body Snatchers, Peeping Tom, Psycho, Texas Chainsaw Massacre, and others, and were taking new shape towards the end of the 70s, thriving throughout the 80s and beyond. All three share the trope of the (white) female protagonist as the sole and final survivor of violence and terror perpetrated by her antagonist in a gradually heightening order of events – first against her entourage, then against her – before her eventual vengeance and release.

Coined as the „Final Girl“ by feminist film scholar Carol J. Clover in her book „Men, Women, and Chain Saws: Gender in the Modern Horror Film“ (1992), this trope developed into different variations and became a site for the symbolic cinematic (re)enactment of gendered power dynamics that both reflected and shaped social norms within the sphere of American cultural influence.

Foregrounding a female character who first witnesses the horror and (but) then fights back to escape what Clover calls „abject terror“, the Final Girl mechanism allows the male audience, so concludes Clover, a degree of identification with the female survivor and avenger – at least superficially. This identification, however, is mostly possible due to the attributes given to the character which, in fact, support and confirm the male gaze and its patriarchal structure. Often, the Final Girl survives because she is virginal or less sexually active than her peers, thus implying morality as a pass to survival (Laurie and Alice, respectively), or she embodies features coded masculine (Ripley). Likewise, she survives despite her vulnerability, coded feminine, being put on full display.

Further analyzing the mechanisms underlying the genre, film scholar Barbara Creed, in „The Monstrous-Feminine“ (1993), argued that horror productions of the era were structured around the subliminal tension between what was understood as social norms, order, the rule of law – belonging to the patriarchal and deemed positive – and a „monstrous-feminine“ assuming various forms (Woman as Possessed Monster; Witch; Monstrous Womb; Castrating Woman; Vagina Dentata; Archaic Mother), constantly threatening the former. Significantly, all the tropes enumerated by Barbara Creed have a long history that political philosopher Silvia Federici traces in the practices of capital accumulation during the late Middle Ages through the 17th century. These included devaluing women’s labour, controlling their bodies, rationalising reproduction, and subjecting them to torture, dispossession, enslavement, persecution, shaming. Inflicted upon women and later continued by European slave traders in colonised territories, these practices laid the foundation for modern social organisation.

In her analysis, Creed relied not only on Freud, but also, and particularly, on literary theorist Julia Kristeva’s book-length essay „The Powers of Horror“ (translated into English in 1982). In it, Kristeva conceptualises the abject as a psychoanalytic framework that accounts for the visceral mix of revulsion and fascination arising when the boundaries of subject and order are breached. Most forcefully, abjection occurs at the level of the body, and in a further step, extends analogously to social life, determining what is considered acceptable and what is repressed. Blood, excrements, and other substances, death, decay, blur the line between the clean and what Kristeva calls the „improper/unclean“, and between the formation of the self and its undoing. Two main strands of Kristeva’s book, which Creed employs in her own study, are the discussion of ways in which women have historically been represented as „impure“ and coded as sites of bodily excess – thus being associated much more strongly to the abject than men. Further, the concept of borders, whose trespassing (in Kristeva’s words, the abject is the in-between, the ambiguous) becomes central to the construction of the monstrous in horror films.

Revisiting the imagery of horror films from the late 70s and 80s today means reconsidering the representations of women that shaped the childhood and adolescence of Herfeldt’s generation and tracing how they have progressed, or regressed, over time. By framing sculptural work that might at first seem abstract – or, say, socially disconnected – through the show’s title and situating it within the implied imaginary, makes a strong statement on Lisa Herfeldt’s behalf about how her work should be approached. Yet, so does, on closer inspection, her use and juxtaposition of slick, neat, rigid industrial materials like acrylic glass and aluminium with less stable, less orderly ones such as silicone foam – whose appearance vaguely and eerily recalls organic matter and which is used for prosthetics – and silicone seal, the shape-shifting „stuff“ that fills gaps and in-betweens. Alongside the vertically erected silicone ellipsoid, additional tubular silicone and silicone mouldings hang limply, wind, constrict, or fracture within the confines of horizontal acrylic glass containers, distributed on the walls as architectonic interventions. They show up again as images – mounted horizontally on a wall, each on its own acrylic glass support, perhaps recalling enlarged Petri dishes. An aluminium folding-screen stands decorated with a repeating pattern: the enlarged image of a brown mark left by water damage on an apparently soaked plasterboard. Camouflaged behind the reduced aesthetic, subdued colour scheme, and their industrial origins, which seemingly unifies them, the connotations of these objects inevitably clash once the contrasts offered by their functions and symbolic properties become evident. Materials usually regarded as stable and standard, evoking, so to speak, an aesthetic of trust, seem to yield to an overbearing feeling of lack – implied by its signifier, the silicone used medically for prosthetics and as a filler in construction. There seems to be a concerted yet improper effort to contain the spreading damage and precariousness.

Returning to „Final Girl“, the hermetic yet alluring ellipsoid shape evoked at the beginning seems to condense a wide array of projections most effectively. Like the construct of the Final Girl in horror films, its shape serves as a screen onto which fantasises, meanings can be inscribed.

A moment of reflection is worth having here.

What becomes clear is a necessity of reevaluation, because at its core, what is truly abject – and what, slowly, through these mechanisms of projection, seeps into consciousness just like the gradually spreading brown mark of water damage – is the precariousness of living.

Mihaela Chiriac

-

Lisa Herfeldt

‘Alice, Laurie & Ripley’ 2025

(Installation View) -

Lisa Herfeldt

‘Alice, Laurie & Ripley’ 2025

(Installation View) -

Lisa Herfeldt

‘Alice, Laurie & Ripley’ 2025

(Installation View) -

Lisa Herfeldt

‘Alice, Laurie & Ripley’ 2025

(Installation View) -

Lisa Herfeldt

‘Alice, Laurie & Ripley’ 2025

(Installation View) -

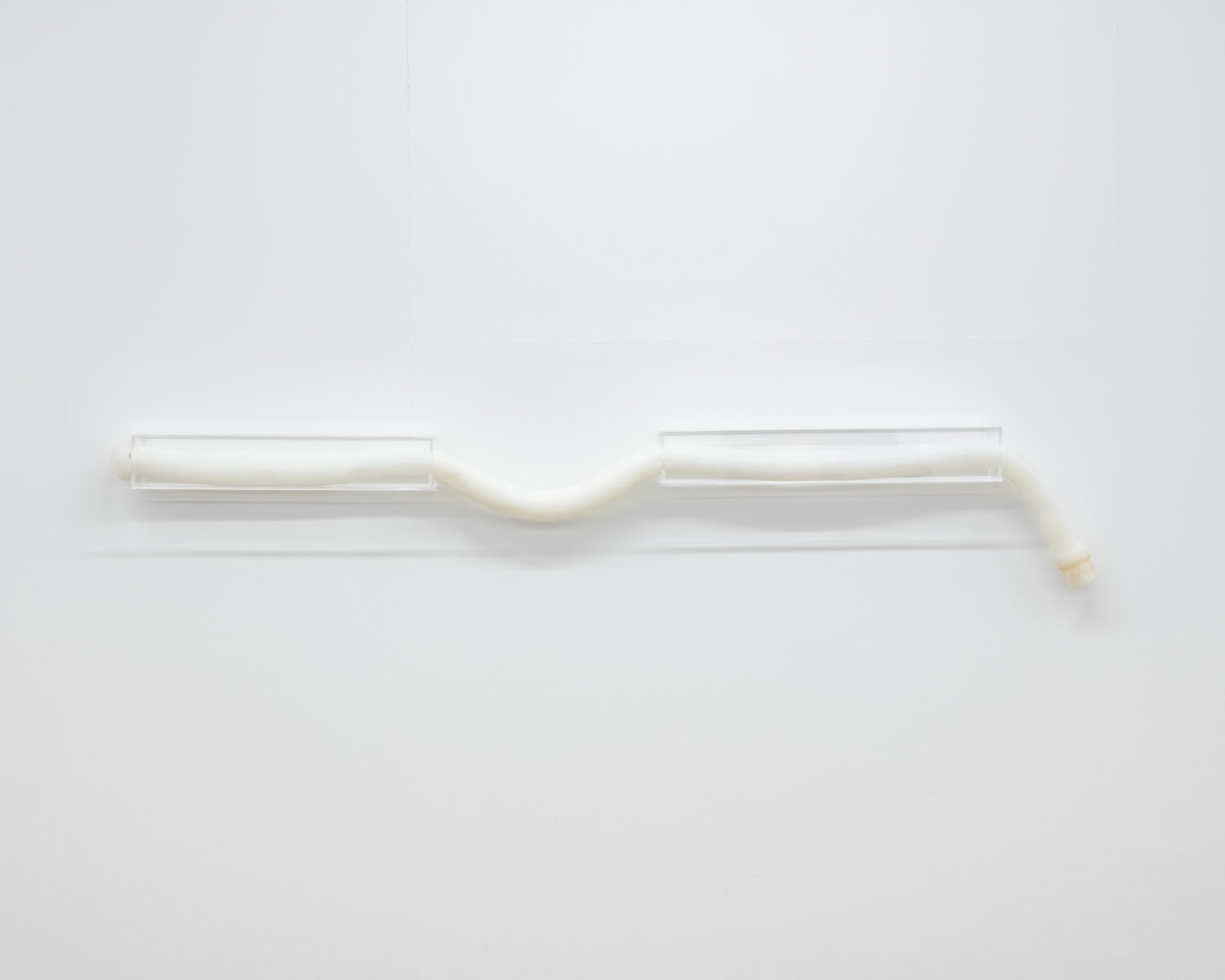

Lisa Herfeldt

Transmission, 2025

Silicone foam, acrylic glass

23 × 146 × 8 cm

9 ¹⁄₁₆ × 57 ⁷⁄₁₆ × 3 ³⁄₁₆ in -

Lisa Herfeldt

Challenger, 2025 (detail) -

Lisa Herfeldt

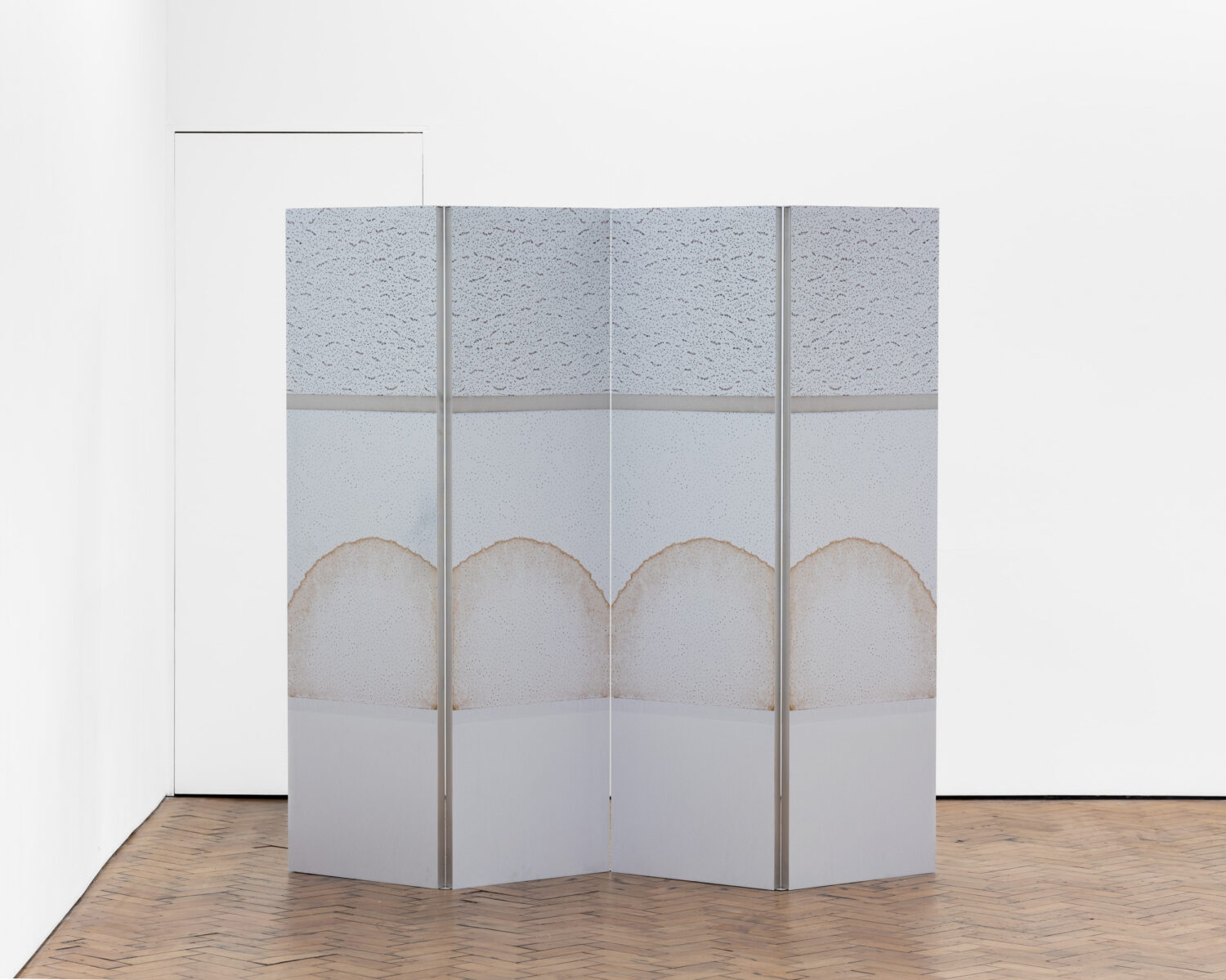

Paravent, 2025

Inkjet print on aluminium

175 × 200 × 3 cm

68 ⁷⁄₈ × 78 ³⁄₄ × 17 ²³⁄₃₂ in -

Lisa Herfeldt

Paravent, 2025 (Installation view) -

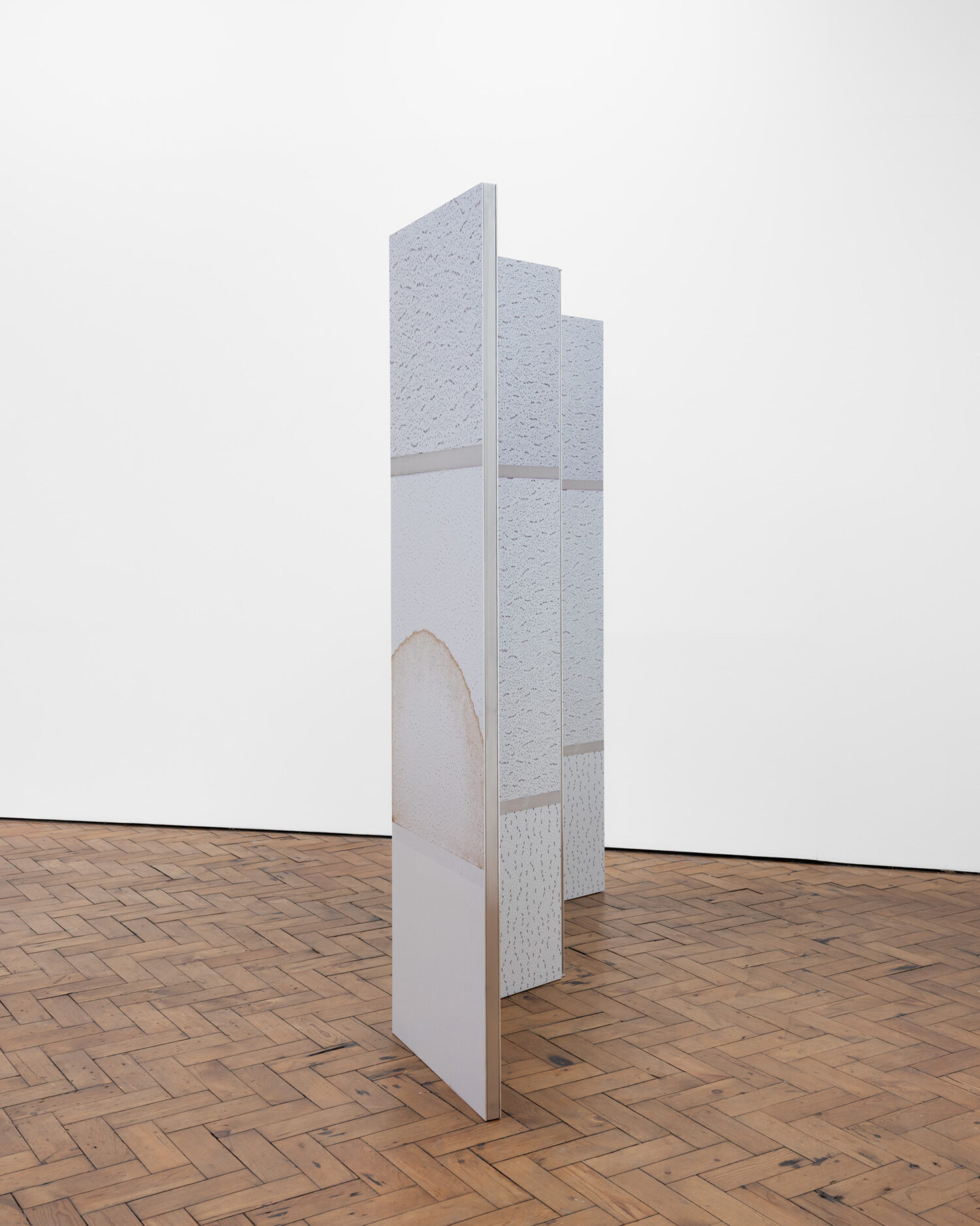

Lisa Herfeldt

Paravent, 2025 (Installation view) -

Lisa Herfeldt

Paravent, 2025 (Detail) -

Lisa Herfeldt

Final Girl, 2025

Silicone foam, acrylic glass & polymer plaster

185 × 32 × 32 cm

72 ¹³⁄₁₆ × 12 ⁵⁄₈ × 12 ⁵⁄₈ in -

Lisa Herfeldt

Final Girl, 2025 (Detail) -

Lisa Herfeldt

Final Girl, 2025 (Detail) -

Lisa Herfeldt

Final Girl, 2025 (Detail) -

Lisa Herfeldt

Challenger, 2025

Silicone sealant, acrylic glass

13 × 83 × 9 cm

5 ¹⁄₈ × 32 ¹¹⁄₁₆ × 3 ⁹⁄₁₆ in -

Lisa Herfeldt

Challenger, 2025 (Detail) -

Lisa Herfeldt

Challenger, 2025 (Installation view) -

Lisa Herfeldt

Echo 1, Echo 2, Echo 3, 2025

(Installation view) -

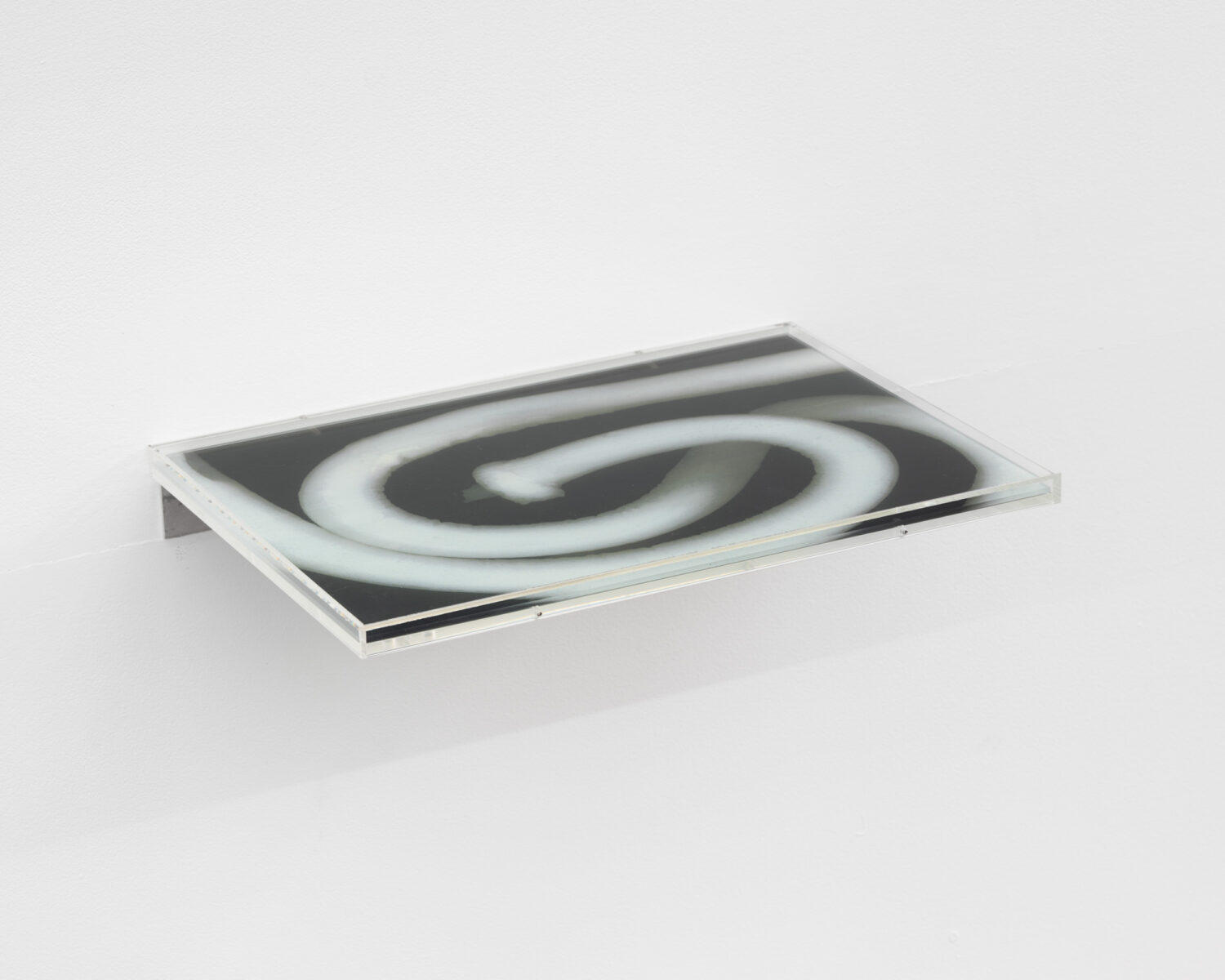

Lisa Herfeldt

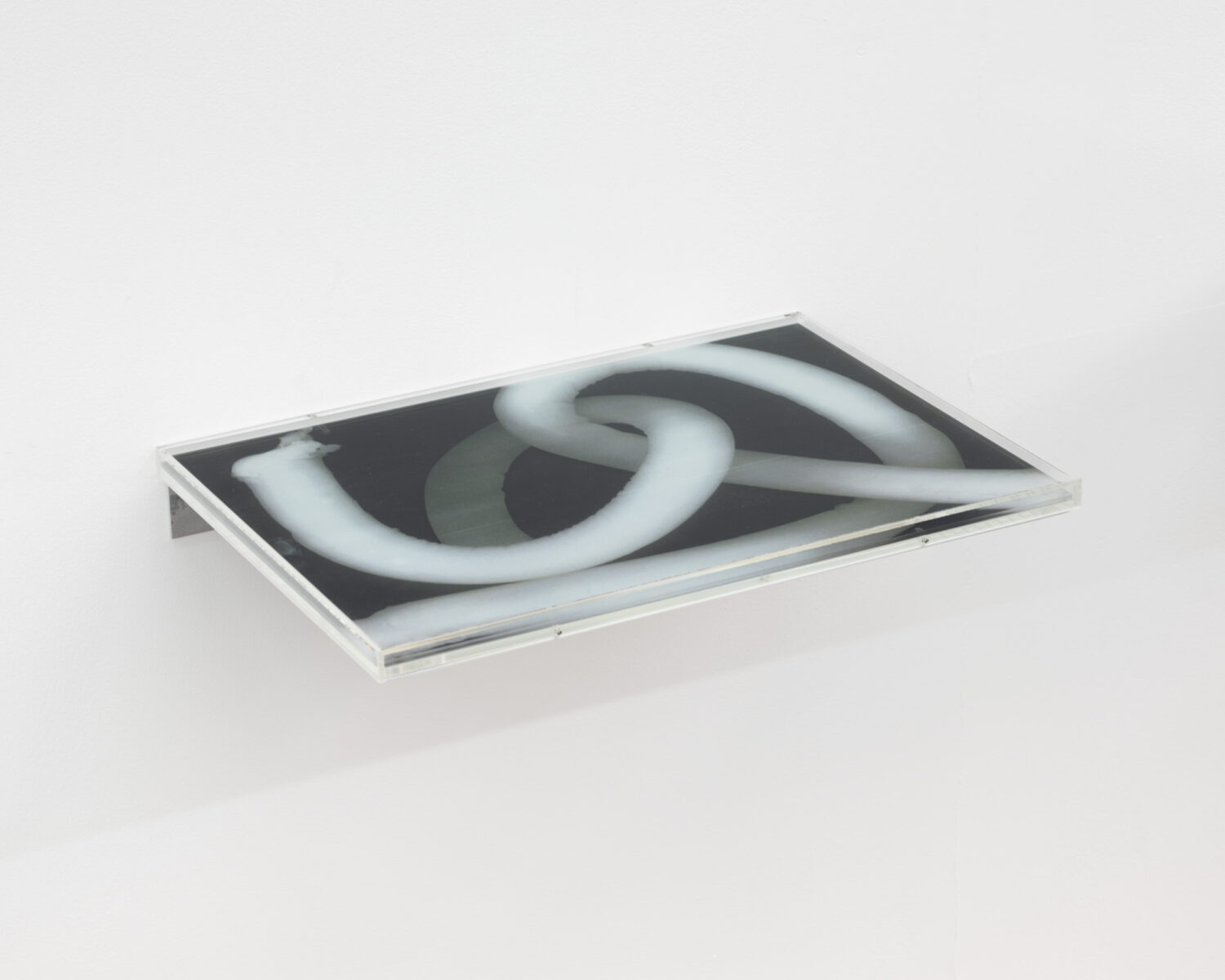

Echo 2, 2025

Print on acrylic glass, acrylic glass frame, aluminium

Edition of 2 + 1 AP

41 × 29.1 × 20 cm

16 ¹⁄₈ × 11 ⁷⁄₁₆ × 7 ³⁄₈ in -

Lisa Herfeldt

Echo 1, 2025

Print on acrylic glass, acrylic glass frame, aluminium

Edition of 2 + 1 AP

41 × 29.1 × 20 cm

16 ¹⁄₈ × 11 ⁷⁄₁₆ × 7 ³⁄₈ in -

Lisa Herfeldt

Echo 5, 2025

Print on acrylic glass, acrylic glass frame, aluminium

Edition of 2 + 1 AP

41 × 29.1 × 20 cm

16 ¹⁄₈ × 11 ⁷⁄₁₆ × 7 ³⁄₈ in